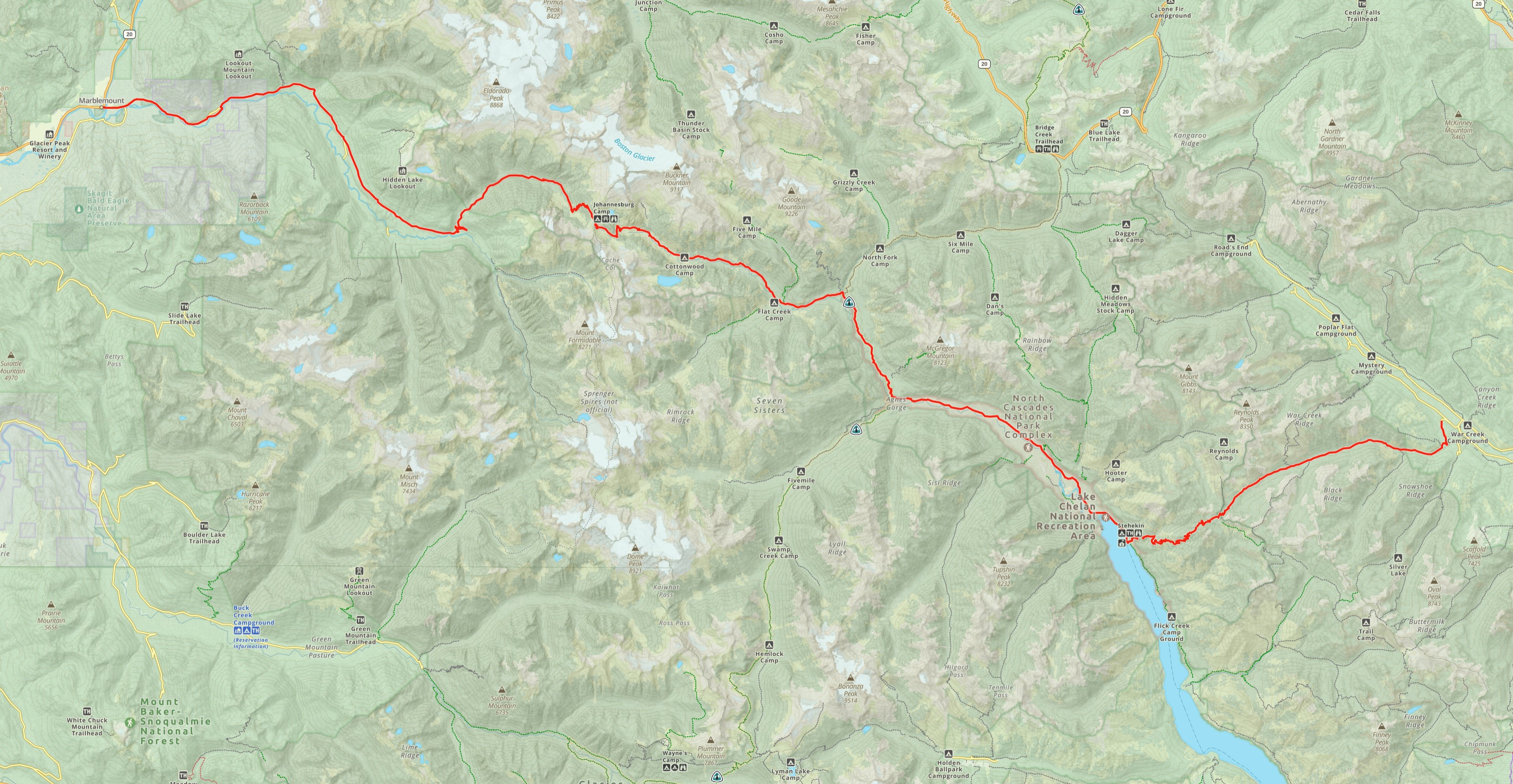

(mm 2576.5) For just under 5 miles, from High Bridge to Bridge Creek, you will be walking in the footsteps of untold numbers of predecessors; natives, explorers, miners, and hikers seeking Cascade Pass at the headwater of the Stehekin River. We've already discussed the natives who used this route, so here I will mention the non-natives; explorers and miners.

The first two known Anglo-Europeans to cross the North Cascades via the Stehekin River valley both traveled to Cascade Pass which is 12 miles and 4,584 ft beyond the Bridge Creek Campground.

1814 Alexander Ross

Scotsman Alexander Ross was employed by the Pacific Fur Company, he took part in the founding of Fort Astoria and Fort Okanogan, both on the Columbia River. During the war of 1812 British troops took Astoria without opposition. In 1813 Ross’s employer was forced to sell the company to the British North West Company. Ross stayed on with the company managing Fort Okanogan.

At the age of 31 he set out from Fort Okanogan with three native guides to find an overland route to the Pacific. They got to within about four days of the ocean before turning around.

The war ended Dec 1814 and six years later the company was absorbed by the Hudson’s Bay Company which continued to employ Ross at Fort Nez Perce. He left very few notes about his journey over Cascade Pass.

1882 First Lt. Henry Hubbard Pierce

The second non-native known to have crossed was US Army First Lt. Henry Hubbard Pierce. Like Ross, he too was following orders to scout and document a route to the Pacific. Along with Pierce were a topographical assistant, Alfred Downing; an assistant surgeon, George F. Wilson; two enlisted men (musician Alford, and Sergeant Worrell). Another lieutenant, George Backus, Jr., joined the group on the way.

For some reason they did not travel Lake Chelan to Stehekin, but chose the extremely difficult route over War Creek Pass and Purple Pass, camping at today’s Purple Point in Stehekin. From there they followed the same route Ross had 68 years earlier.

The expedition spent two nights (Aug. 25 & 26) below Sahale Arm where the group nearly quit and headed back to Colville. Pierce and Alford convinced the group to press on. They traversed Cascade Pass on August 27, across a ¼ mi wide snowbank. Pierce describes an extremely difficult crossing with horses.

Unlike Ross, Pierce did not turn back. He did make it to the Pacific. To descend the west side of Cascade Pass, they removed the packs from their animals and lead them down unburdened. They followed the Cascade River to Marblemount. In Marblemount they purchased some canoes and rode the Skagit River to a logging camp in Sterling. From there they took a steamboat further down river to Mount Vernon, arriving September 5th.

Pierce’s 27-page report was submitted on December 13th, 1882. He died of Tuberculosis seven months later near Foster Creek (Near Bridgeport, WA) at the age of 43. The Oregonian newspaper printed an obituary on July 27, 1883

His full report is not available online but can be requested from Washington State Archives in Olympia.

Gold! (and silver, copper, lead, and molybdenum)

It’s difficult to say exactly when the first prospectors were in the area, but there were certainly a lot of people exploring the area for mineral wealth in the last quarter of the 19th century. It’s what seems to have originally brought the people who ultimately settled in the Stehekin River Valley as homesteaders.

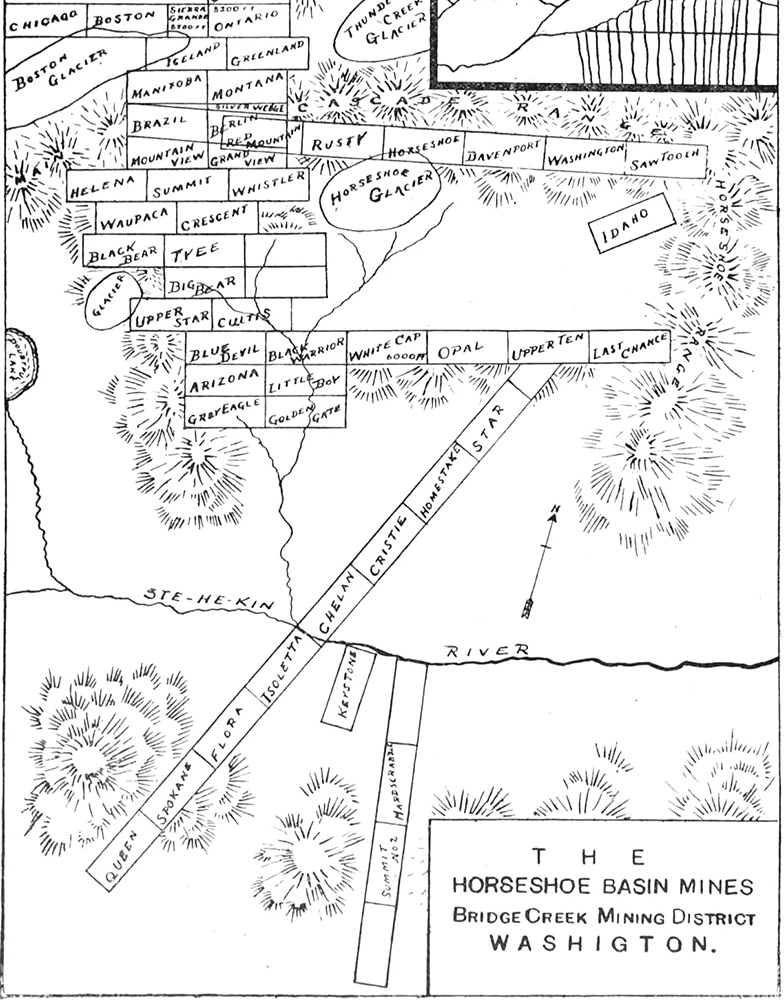

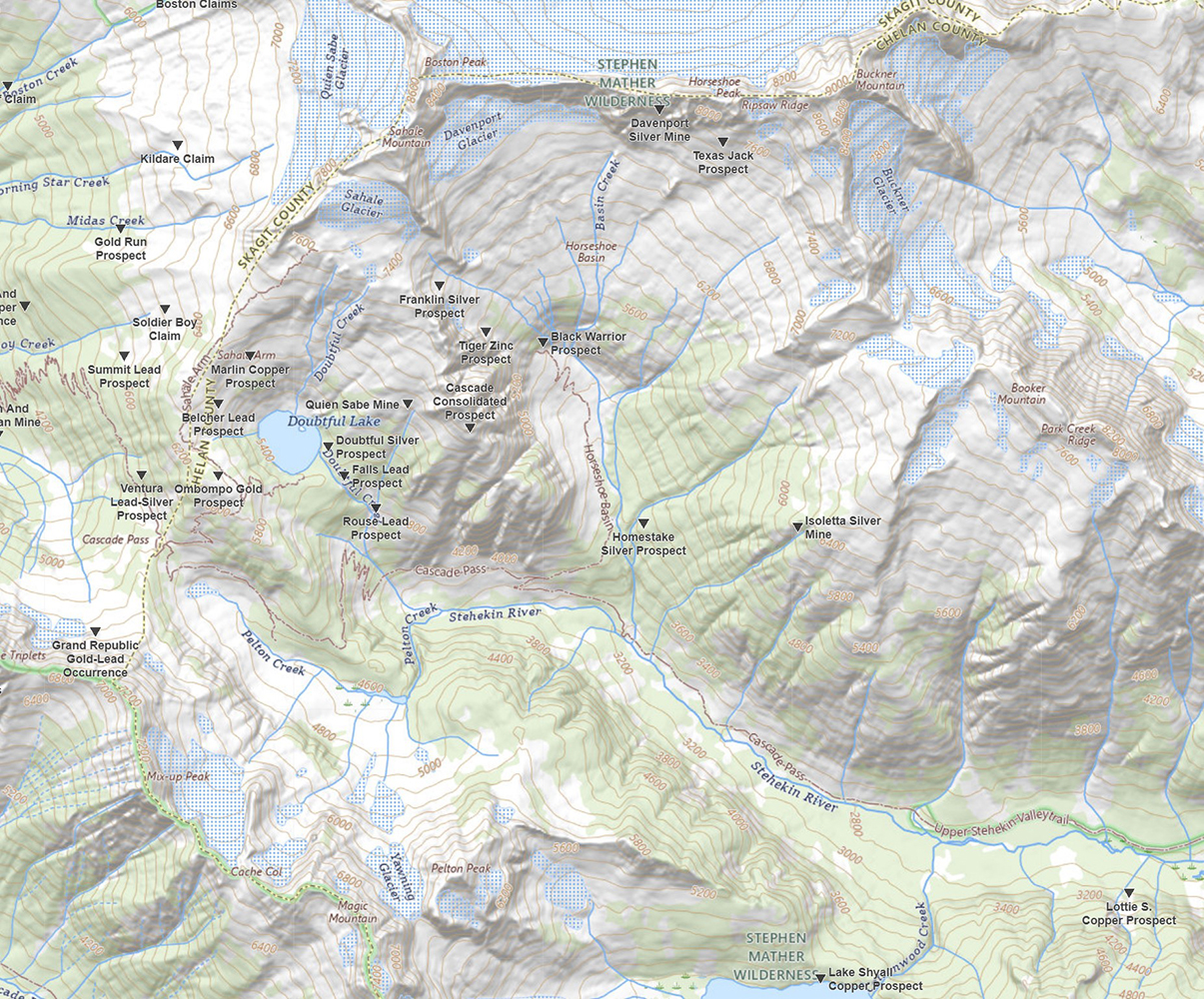

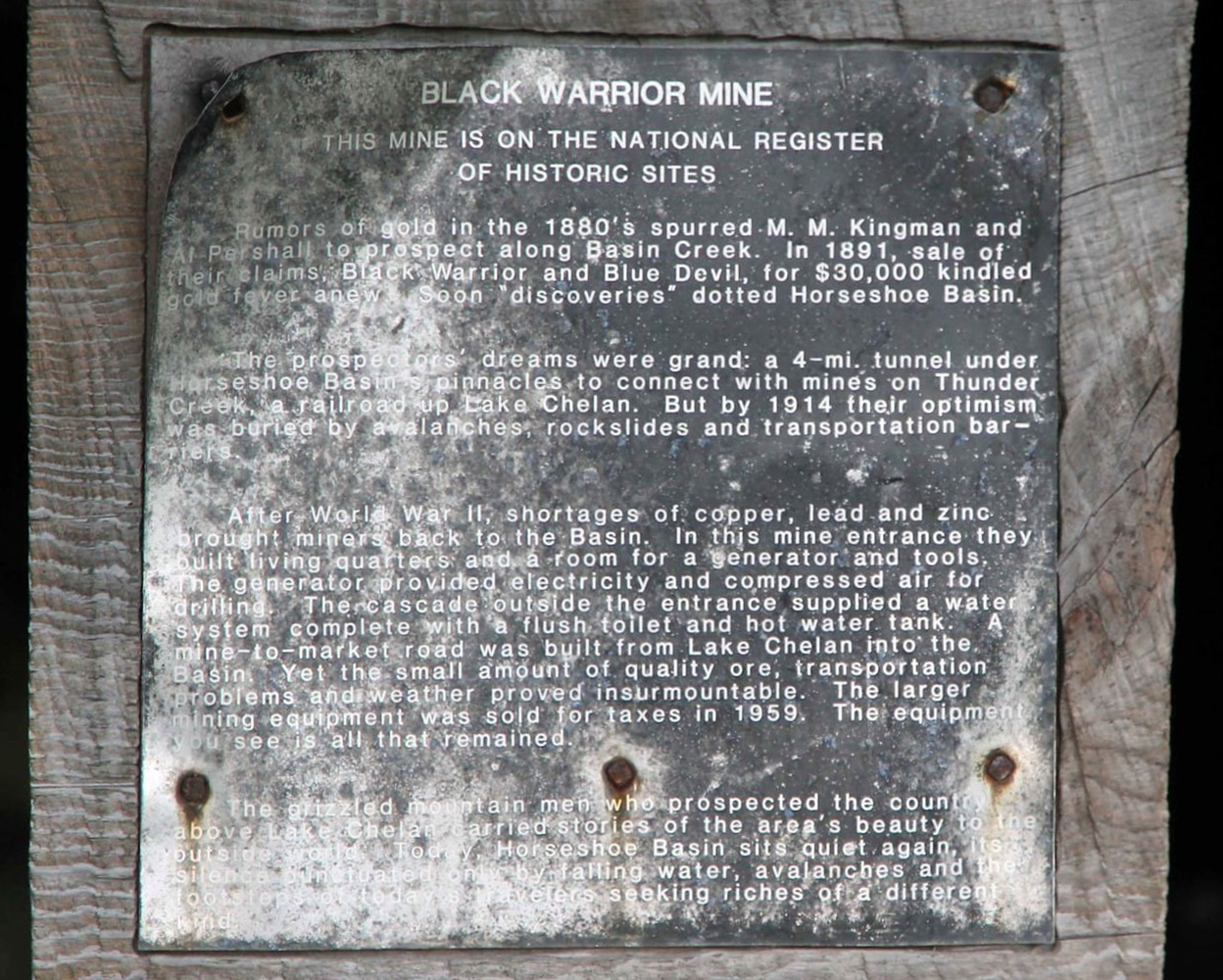

Mining claims near the headwaters of the Stehekin River, in the vicinity of Doubtful Lake and Horseshoe Basin, were both the earliest and the most worked. By the late 1880s supplies were being shipped by steamboat up the lake from Chelan, then packed into the mountains. Stehekin served as a center point between Chelan and the mining claims. While mining activities continued into the early 20th century, most companies failed to profit.

The history of the road from Stehekin up the Stehekin River is directly tied to the history of the mines, and also to the history of nature’s constant efforts to erase it.

Bridge Creek Camp

Bridge Creek flows into the Stehekin river and is named for the need of a bridge at that spot for the road to continue up the north side of the Stehekin River toward Cascade Pass. Bridge Creek Camp was a camp long before the PCT or the CCT. It was a base of operations supporting the mines in the area. There were many cabins here. Today, observant campers at Bridge Creek Campground might notice the multitude of decaying structures and equipment around the area, and they might also notice when the trail widens in places revealing remnants of the old wagon road.

The Buckner family had a cabin here at the mouth of Bridge Creek built around 1900.

Timeline of the road beyond High Bridge

1905 May - A telephone line was run from Stehekin to Bridge Creek Camp by H.F. Buckner.

1913 - The road was officially named State Road #13 Cascade Wagon Road. The law describes the intent of it going to Marblemount which indicates that no one actually inspected the nearly impossible route over Cascade Pass.

1947 - The road all the way to Black Warrior Mine was passable by wagon, having been improved by miners. Maintaining the road was so much work, they stopped doing so the following year.

1948 - A catastrophic flood of the Stehekin River damaged bridges and roads. This was the beginning of the end for the road past High Bridge. More floods did damage in 1995, 2003, 2006.

1968 - The NPS built a new bridge over Bridge Creek and made usable the road all the way to Cottonwood Camp.

1970 April - The Stehekin Valley Road was transferred from Chelan County to the NPS. It was one of the most expensive roads for the county to maintain.

1975 - The NPS built a new bridge at High Bridge.

1991 - The county tried to take back ownership of the road from the NPS because it was not being maintained, but a judge ruled against it in 1993.

1995 - Floods forced the NPS to abandon the road from Bridge Creek to Cottonwood Camp

2006 - After the fourth major flood to damage the road, the NPS officially and permanently closed the Upper Valley Road at High Bridge. Any maintenance of that road today is done voluntarily by users.

2009- Representative Hastings introduced a bill, HB 2806 that would allow the National Park Service to adjust the wilderness boundary for the sole purpose of rebuilding the closed 2.5 mile section road. The legislation passed the U. S. House of Representatives on Monday, October 26th and moves forward for Senate consideration. (Lake Chelan Mirror, 2009)

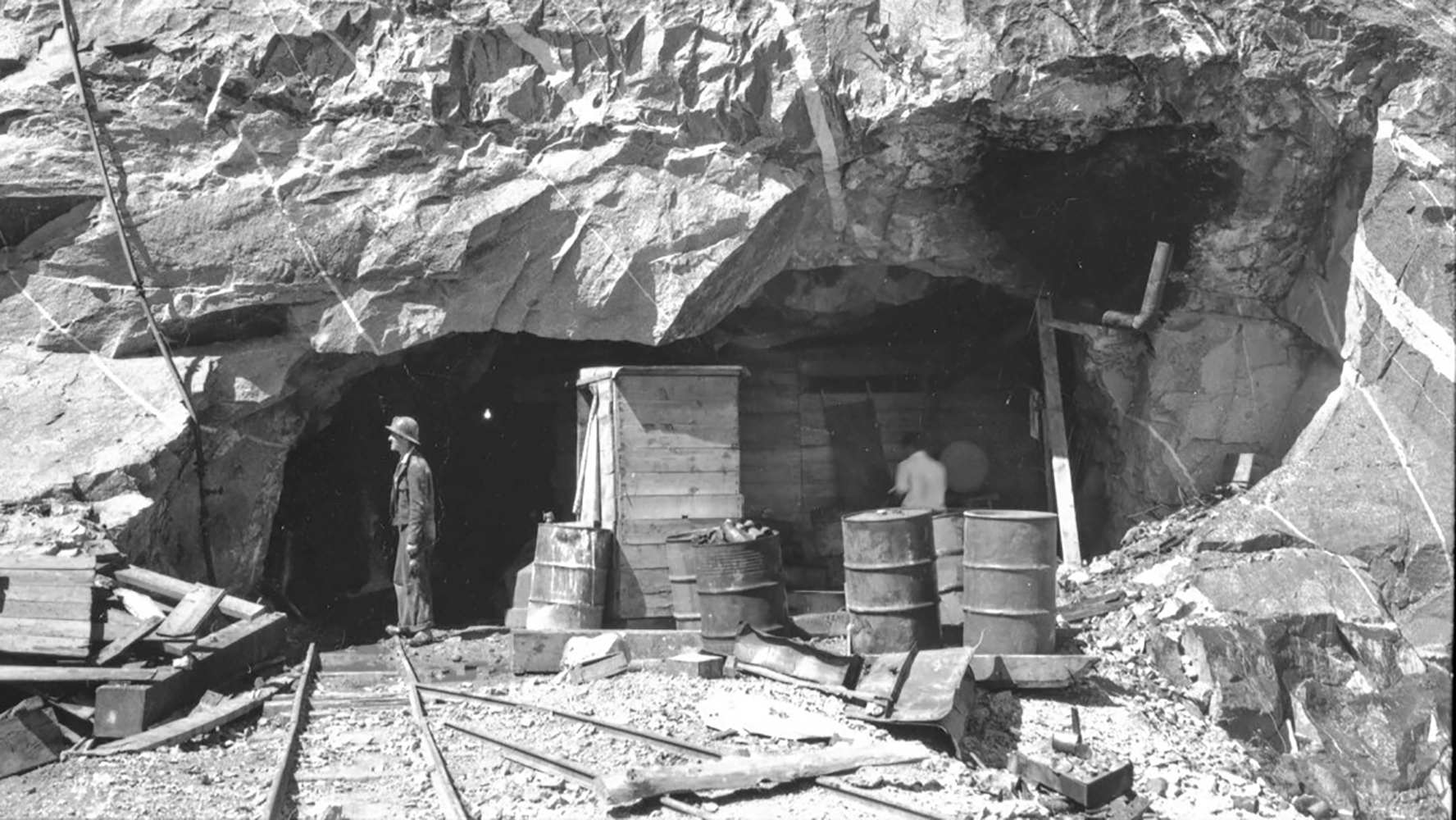

The Black Warrior

The Black Warrior Mine is in Horseshoe Basin, on Basin Creek an upper tributary of the Stehekin River, 10 miles and 3,547 ft from Bridge Creek Campground.

Of all the mines in the Stehekin watershed, the Black Warrior was the most worked. It was discovered and claimed in 1889 by M. M. Kingman and Albert Pershall. Two years later they sold the mine to Markle and MacFarland of Portland for the unprecedented sum of $30,000.

Over time the subsurface depth of the mine reached 220 ft. and extends for a distance of 1,275 ft. The ore extracted produced gold and copper, as well as some lead and silver.

It's ironic to me that this mine is in one of the most beautiful basins anywhere. Camping in Horseshoe Basin is an awe inspiring experience that I think rivals the famous Indian Bar Camp at Mt. Rainier. Four peaks tower almost 5,000 ft above you, showing off their glaciers. In the spring their are nine streams pouring into the valley each with up to eight distinct waterfalls all visible from the basin floor. They are fed year-round by the Sahale and Davenport Glaciers.

The inner tunnel is blocked off so bats can pass but not humans.

The inner tunnel is blocked off so bats can pass but not humans.

You can find the mine above the pile of waste quartz, at the bottom of the rock wall, on the left (west) side of the creek. 48°28'46.65"N, 121° 1'29.63"W

The route shown on GaiaGPS is accurate and will take you directly to Black Warrior. Almost every trip report from the basin that I have read mentions a bear encounter, but I saw no reports of charges.

Black Warrior Mine by Andy Porter. Video of Black Warrior Mine

Davenport Ledge

When I first started reading about another heavily worked mine in the upper part of Horseshoe Basin, I did not believe a mine could be up so high. But sure enough, I found trip reports made by climbers who had reached the mine.

The Davenport Ledge Mine was also discovered by Kingman and Pershall. In 1897 they dug a level 50-foot tunnel into an exposed galena vein (lead ore). They continued to work the mine, along with C.E. Gable, through 1904 when H.F. Buckner accepted the contract and began work with 8 other workers. The tunnel was then about 100' into the side of the mountain. Buckner had previously built Stehekin's first water works and had electrified the town.

The last report of the tunnel depth was 475 ft. in 1906. The last report of the mine at all was in 1907. The Stehekin Newspaper misreported the mine at 8,000 ft. more than once, when in fact its entrance is at 7,000 ft. 48°29'27.82"N, 121° 1'2.57"W

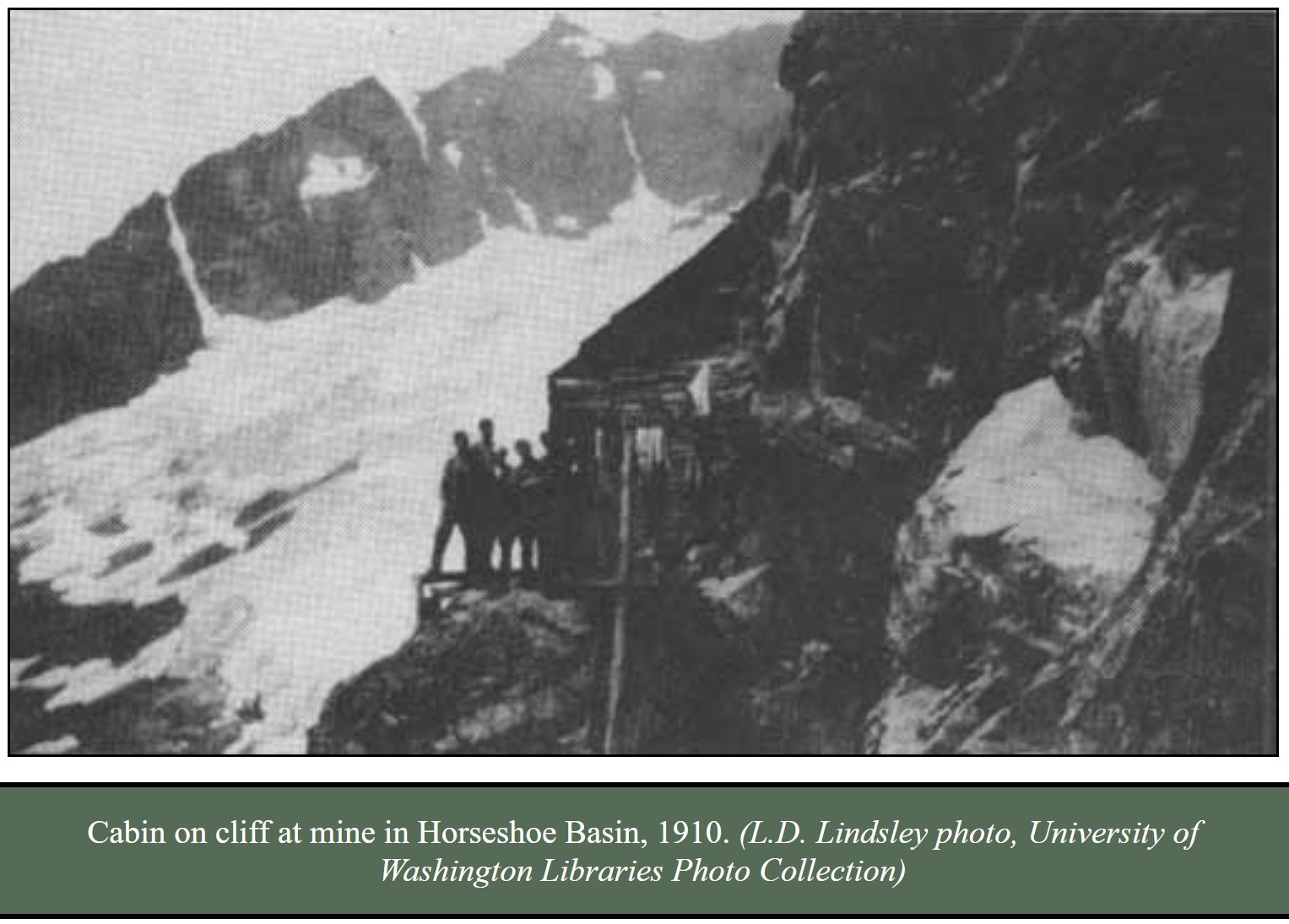

Photographer Lawrence D. Lindsley visited Black Warrior and Davenport around 1910 and remarked how a cabin was wired to a rock ledge to keep it in place. He entered the cabin by a ladder through the floor. Lindsley also mentioned large cabins of a mining supply camp on the Stehekin River at the bottom of Horseshoe Basin at today's Basin Creek Campground.

And that is why there was already a trail from High Bridge to Bridge Creek Campground.