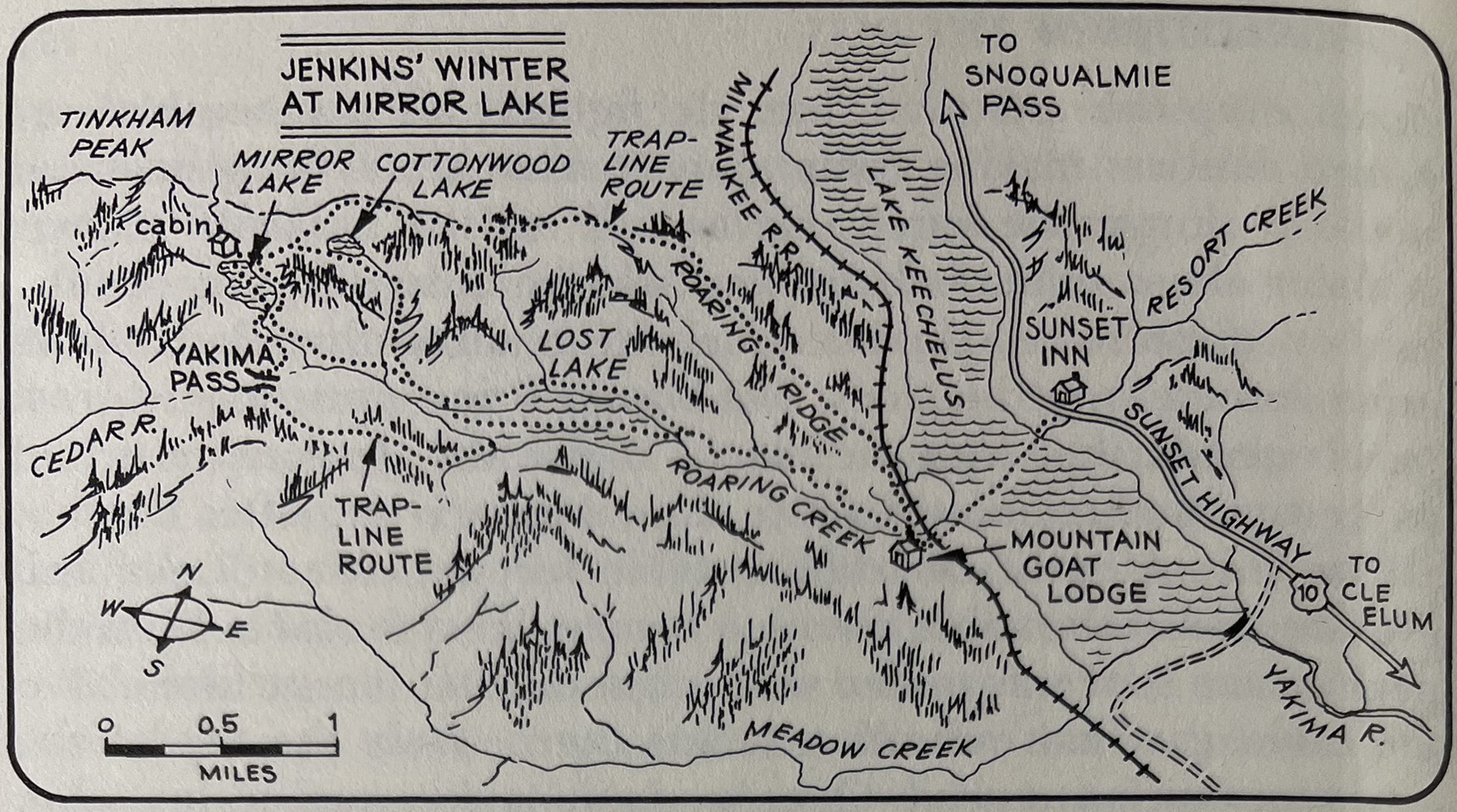

Eight trail miles south of Snoqualmie Pass, PCT hikers walk the east bank of Mirror Lake. While there, hikers might look to the rocky outcropping at the north end of the lake and think about Morris Jenkins and Warren Haase who lived in a cabin there over the winter of 1929.

The two worked on the road that is now Interstate 90 the summer of 1929, earning 50 cents an hour. After the summer work stopped, they moved into a cabin built on a rock ledge on the north shore of Mirror Lake, below Tinkham Peak, next to a small creek. The cabin had been built by Lawrence Davis, the caretaker of the Mountain Goat Lodge on Lake Keechelus at the mouth of Roaring Creek. Davis offered the cabin to Jenkins and Haase for the winter.

They used Davis's rowboat to cross Lake Keechelus to get supplies from Sunset Lodge, at the mouth of Resort Creek. Then they packed their supplies from Mountain Goat Lodge up to the cabin, including the tin stove they bought.

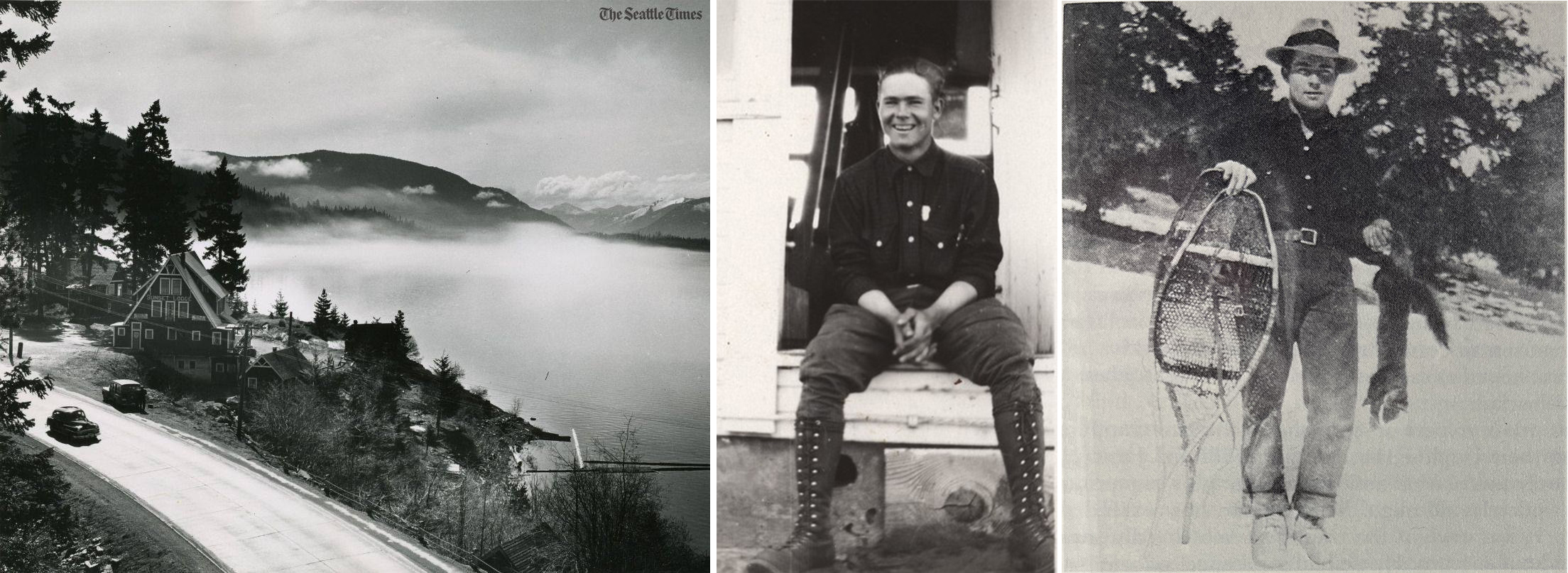

Left: Sunset Lodge years later. Right: Morris with self-made snowshoes.

Left: Sunset Lodge years later. Right: Morris with self-made snowshoes.

The day before the snow started to fall that winter Morris noticed the deer hurrying to Yakima Pass and down the Cedar River to lower ground. He learned to watch the deer for signs of fall snowstorms.

After the snow completely buried the cabin, Morris and Warren would add sections of stove pipe to their chimney to keep it above the snow. Because the cabin was not well insulated, a dome ice cave melted around the cabin. They could walk completely around the outside of the cabin in this dome still buried in the snow. That winter the temperature got bitterly cold, but the cabin stayed cozy buried under the snow.

The two men attempted to live by trapping but only caught a few martins, ermine, and flying squirrels - not enough to support two men, so Warren left in early January for a job building the Rock Island Dam on the Columbia River, and Morris continued alone at Mirror Lake.

One day the Morris returned to the cabin to see two sets of ski tracks that came down from the ridge, over their cabin, and across the frozen lake. He felt sure these skiers had no idea the cabin was even there, and he was sad to have missed the potential visitors.

Reading Morris's accounts of that winter in interviews, he seems very lucky to have survived it. He survived being caught in one avalanche and had near-misses with others, and he had numerous harrowing accounts of crossing Lake Keechelus in various states of frozenness, both on foot and in the rowboat. He suffered severe frostbite damage to his feet that took six months to heal.

News of Morris surviving that winter alone at Mirror Lake ultimately landed him a job with the USFS the following year, 1930, as a horse patrol ranger based in Easton. He returned to his home state Idaho in the winters. In 1943 he began working instead for the Northern Pacific Railroad managing the large land grants given to the company, living in Cle Elum. He retired as a District Forest Manager for Northern Pacific after thirty years.

Morris hiked some of the CCT in 1966 and in 1981, at the age of 72, Morris and a friend hiked Section J of the PCT and got caught in an unexpected snowstorm. Cascade weather is as capricious as ever and can cause problems even for the experienced.

Morris kept diaries and gave multiple interviews, some recorded on video and archived at Central Washington University. [1] [2]

To me it's sad to hear him talk in those videos about how the area has changed and how he misses the animals and old growth that are gone now. He also seems to regret having to trap to subsist. He said he would never trap unless he had to survive. In one of the videos he climbs the peak just south of Yakima Pass at the age of 84. Morris died in 2007 at the age of 99.

Looking down on Mirror Lake from Tinham Peak, Cottonwood lake on the left and Lost Lake on the upper right.