(mm 2467.0) As you descend the PCT towards Stevens Pass, stop for a moment and look NW as far up the valley as you can. It happened a bit further down the valley than you can see from here, just out of sight. That is the location of the deadliest avalanche in US history. 96 people died above the NW bank of the creek that starts at Stevens Pass and parallels the US-2 highway.

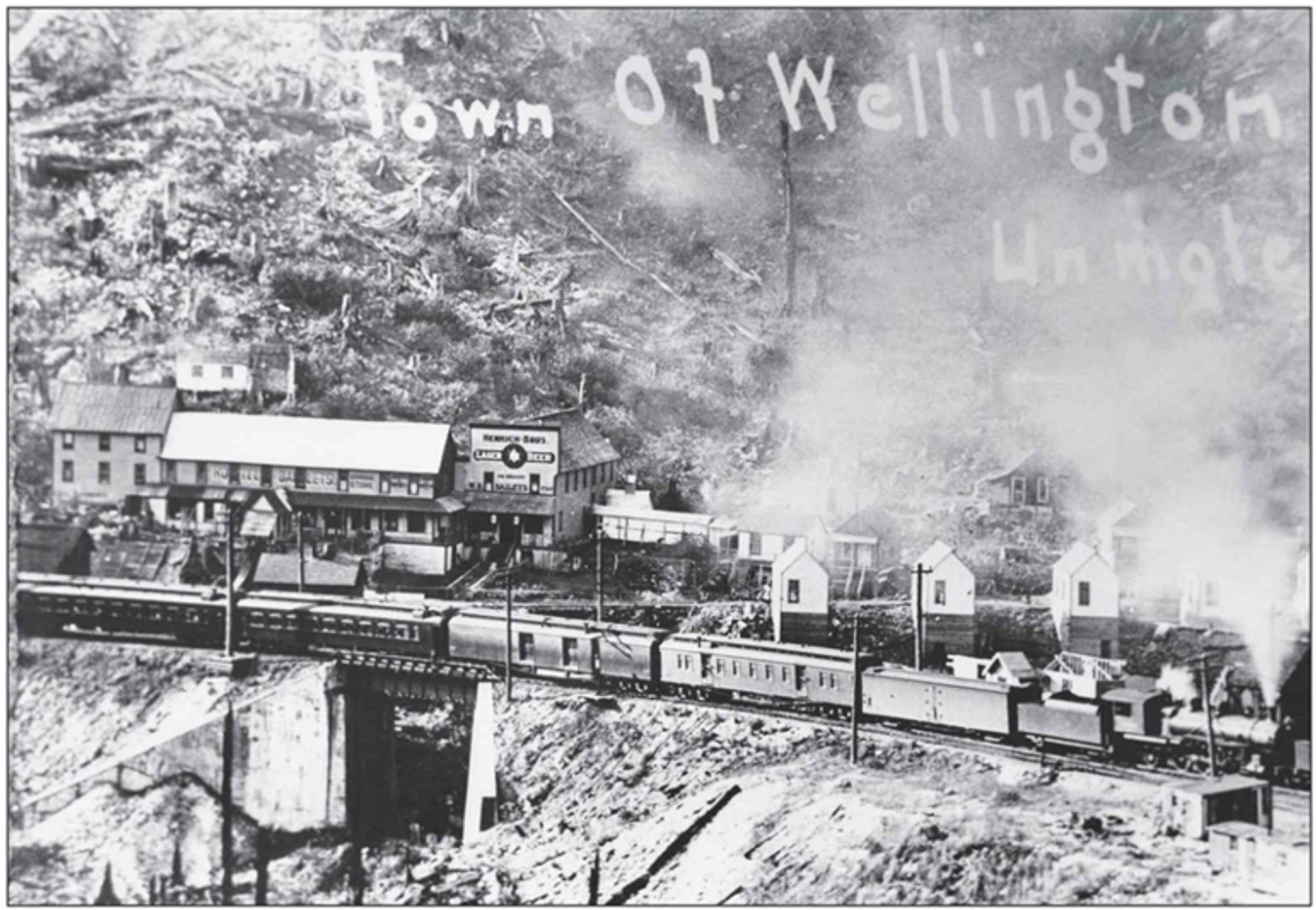

1907, Three years before the Wellington disaster

An eastbound train left Skykomish in a December blizzard with drifting snow filling the cuts as fast as they were plowed. It took five hours to cover the 12 miles to Scenic where the crew was reluctant to continue the 9 miles to Wellington. The dispatcher insisted however, and the train bore on proceeded by a rotary snow plow.

About two miles short of Wellington an avalanche sealed off the entrance to a snow shed just cleared by the advancing snowplow, separating the train from the plow. The engineer quickly backed up the train into the snow shed from which it had just emerged. More slides roared down to enclose the train into the snow shed, unable to move in either direction.

There it remained for 10 days at which time the crew and passengers walked out to Wellington. The train was dug out two days later.

Wednesday, February 23rd, 1910

Two passenger trains, #25 and #27, had been delayed at Leavenworth pending weather information. After some delay the two trains proceeded up the grade together.

Just east of the Cascade tunnel, the two trains were parked on side tracks. It was then learned that a slide near Windy Point blocked the way to the West. The passengers dined in the bunkhouse at "Cascade City" at the east end of the tunnel (today Yodelin Village).

Thursday, February 24th, 1910

As heavy snowfall continued, rotary plows worked feverishly to free the tracks of snow slides, some with boulders and trees in them. But they could not keep up, especially at Windy Point where slides repeatedly filled the tracks as quickly as they were plowed. Finally the depth was more than the capacity of the rotary plow - the plow itself was being buried, unable to expel the snow. So, shovelers were called in from Wellington to help. The crews were unable to keep ahead of the slides. The raging blizzard and heavy snow went on day after day.

As the largest rotary plow was returning to Wellington for coal, a slide 800 feet long and 35 feet deep came down blocking its access to Wellington. Without fuel the plow was useless and trains #25 and #27 now had no hope of proceeding to Scenic.

Friday, February 25th, 1910

Late the next day trains #25 and #27 moved through the Cascade tunnel and were parked on passing tracks beneath the town of Wellington just past the west end of the tunnel.

At Wellington there were three parallel side tracks. On the track nearest the mountain side stood Superintendent O'Neill's private car, 2 box cars, the engine, and three of the electric motors used to haul trains through the tunnel. On the second track from the mountainside stood a train consisting of engine, baggage car, 2 coaches, 2 sleepers, and an observation car. On the third track stood the fast mail train on which were 16 or 18 mail clerks. About 16 track laborers were also sleeping on the train in the day coaches.

After the two trains had passed through the tunnel, an avalanche at the east portal wiped out the station and bunkhouse killing two men. It filled the gulch with 50 feet of snow.

Increasingly apprehensive passengers asked that the train be backed uphill into the Cascade tunnel. Management negated that idea as too dangerous because of the poor ventilation in the tunnel. Food was running low on the trains and in the town of Wellington itself. Meals were served at Bally's Hotel in Wellington and rations were down to two meals a day of potatoes and bacon.

Saturday, February 26th, 1910

When Superintendent O'Neill returned from directing slide removal west of Wellington, to free the rotary plow which was trapped, the station agent told him that the telegraph lines were out and they had no communication in either direction (east or west).

Sunday, February 27th, 1910

An enormous cap of snow was forming on the abandoned switchback above Wellington, hanging precariously and clinging to the sparse timber.

O'Neill and two brakemen elected to walk to Scenic for help. Later that day a party of five passengers set out as well.

Monday, February 28th, 1910

At least two other groups struggled out to Scenic Monday night. They crossed 3 immense slides each about 50 feet deep covering the telegraph poles entirely. When Scenic Hot Springs Hotel was in sight they had to cross a giant slide larger than the rest. Too steep to walk, they could only slide down the mountain side some 2000 feet, some were injured but all made it to Scenic.

Meanwhile, efforts at relief from Leavenworth were stalled too because a snow plow had cleared the tracks as far as Chiwaukum Creek only to have more rock and snow slides come down behind it.

Now snow turned to rain loosening the heavy snows barely clinging to the steep slope above Wellington. That night an electric storm raged. Lightning flashes were vivid, and a tearing wind was howling down the Canyon.

Tuesday March 1st, 1910 4:00 AM – The Avalanche

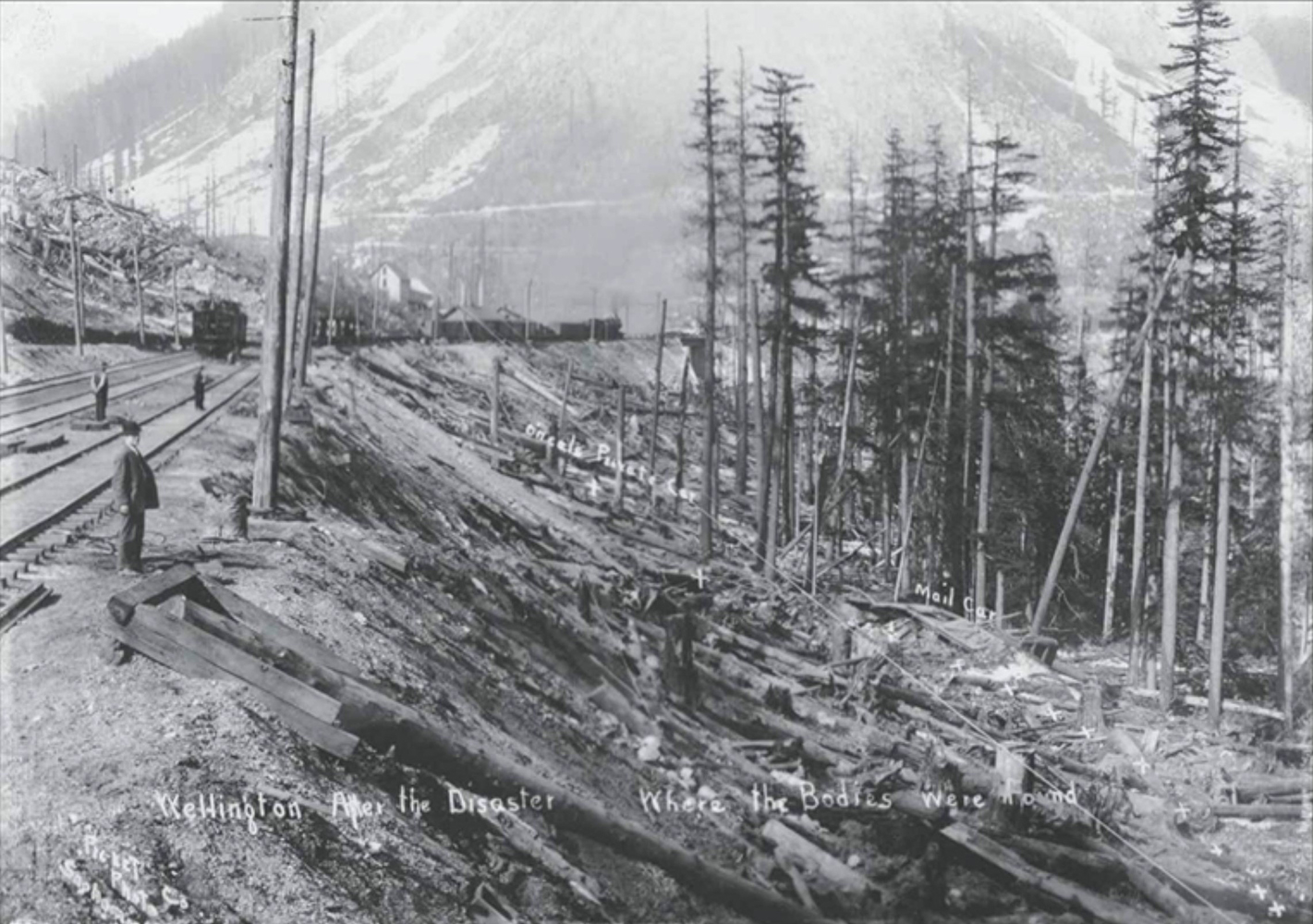

Suddenly there was a dull roar and the sleeping men and women felt the passenger's cars lifted and borne along sideways. When the coaches reached the edge they were rolled nearly 1000 feet laterally and 150 feet vertically and buried under 40 feet of snow, broken trees, and debris. In addition to trains #25 and #27, the slide carried away the motor shed at Wellington and the four motors in it. It also carried away the coal shoots, water tank, and Superintendent O'Neill's car killing his stenographer and cook.

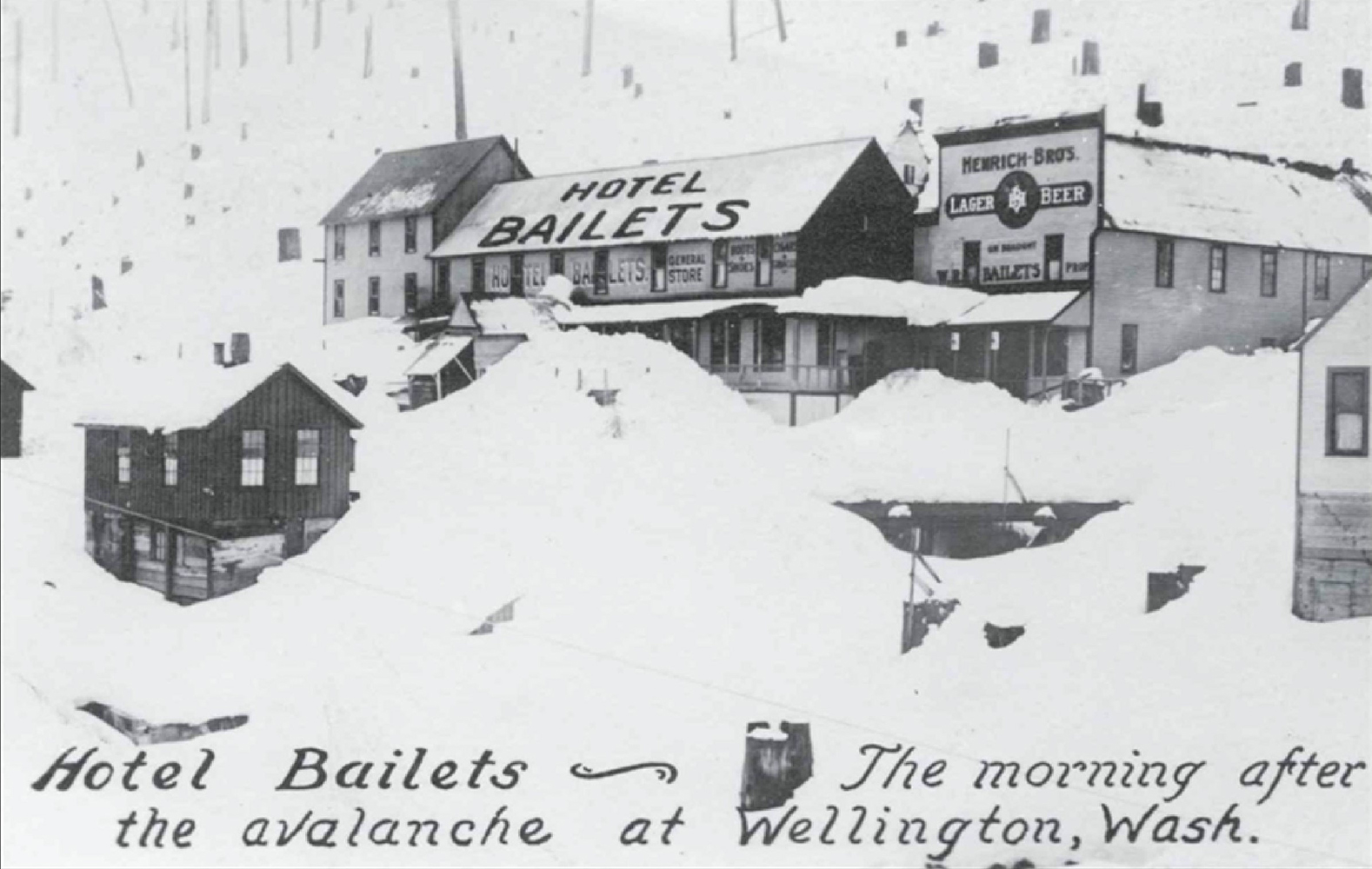

Twenty-three survivors were immediately rescued by people staying at the Welington Hotel, which had not been hit.

One of the survivors was the trains conductor Ira Clay who was sleeping on train #27. He reported hitting the top and bottom of the mail car several times in the descent. The car disconnected after hitting a large tree. “When I realized anything, I felt a sensation of suffocation and I found that I was buried 6 feet under the snow. I dug my way out. The steam locomotive had melted a big cavern where it lay." Clay grabbed a companion to prevent him from falling into the locomotive.

Mrs William Starrett was dug out alive but discovered that her husband, father, mother, and two of her three children had died near her.

On foot, Crewman John Wenzel made it to Scenic Hot Springs Hotel, gasping out the terrible news to Superintendent O'Neill.

Because the telegraph was down, what survivors at Wellington did not learn until later was that one rotary plow at Windy Point was swept away completely by another slide and could not be seen from the tracks. And two other rotaries were lost near the Martin Creek Horsehoe Tunnel.

Wednesday March 2nd, 1910

The hotel at Scenic was the last point with working telegraph to Everet so Superintendent O'Neill directed the relief efforts from there. As slide dangers eased, they resorted to dynamiting through packed snow and ice to enable trains to reach Wellington.

Many of the injured were removed to Leavenworth because conditions on the east slope were better than on the snow choked West side. Nurses and doctors flocked to Wellington. Some of the injured were cared for there and were able to move off the mountain themselves. Most of the dead were taken to Seattle and Everett

150 men, mostly volunteers worked to uncover the dead – a daunting task in the tangle of trees, snow, and wreckage. Most of the bodies were retrieved right away, but a few were not retrieved until late July after the snow had melted.

Afterward

After the accident, an all-concrete snow shed half a mile long was built where the trains had been waiting and many more between Wellington and Scenic. Wellington was quietly renamed Tye so it would not be associated with the tragedy.

In 1929 the town was abandoned because the new longer tunnel had been completed and bypassed the town. The town eventually burned down.

January 1916, during one of the heaviest snowfalls on record (as much as one foot per hour) an avalanche swept a dining car and six day-coaches off the tracks at Corea (near the Deception Creek Trail head). Eight people died and 20 or more were injured.

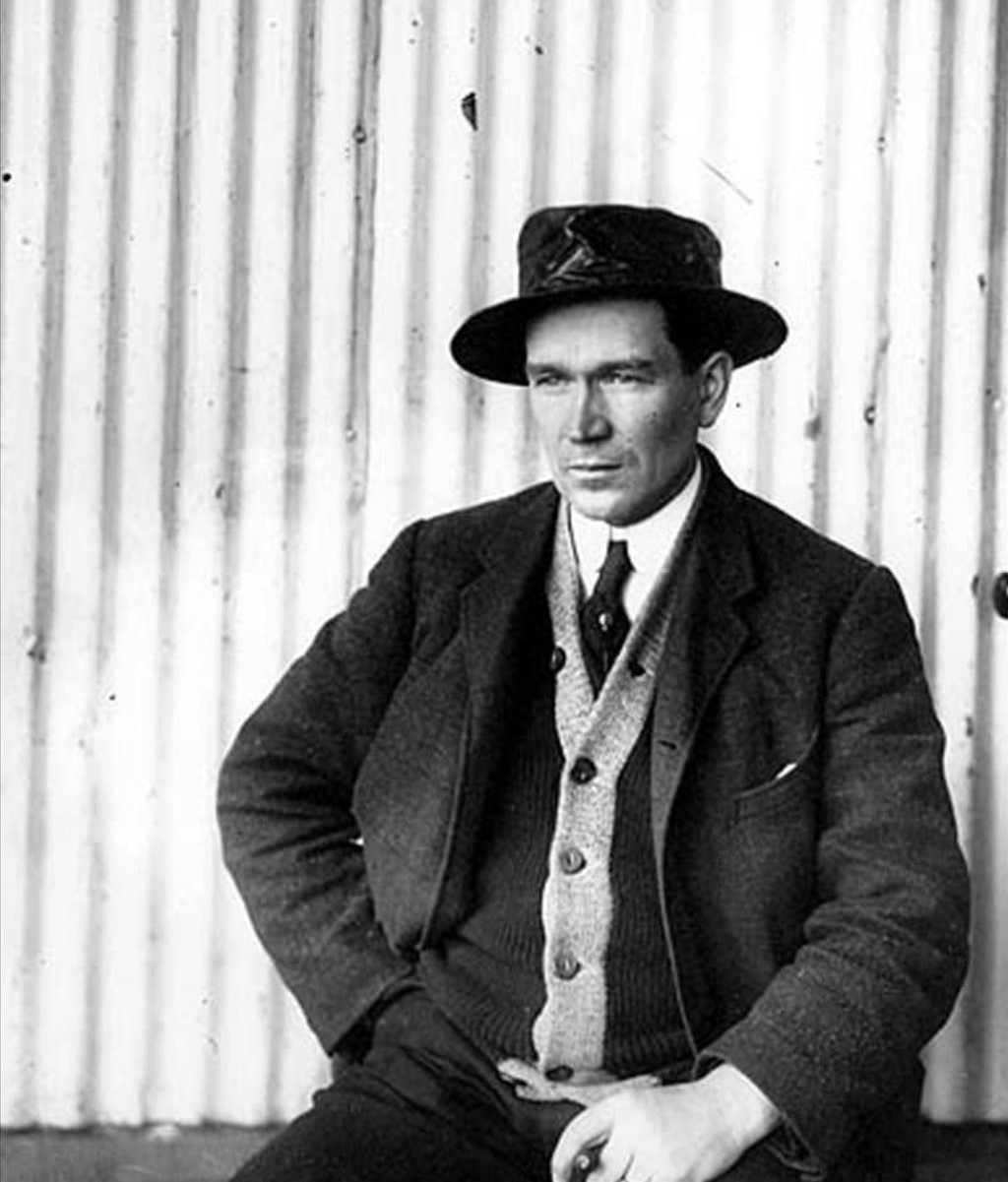

GNR Superintendant James Henry O'Neill